Ancient Cities in Turkey

Hierapolis (Greek: Ἱεράπολις ‘sacred city’) was an ancient Greco-Roman city in Phrygia located on hot springs in southwest Anatolia. Its ruins are adjacent to modern Pamukkale, Turkey.

Hierapolis is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The hot springs there have been used as a spa since the 2nd century BCE, and people came to soothe their ailments, with many of them retiring or dying here. The large necropolis is filled with sarcophagi, including the Sarcophagus of Marcus Aurelius Ammianos.

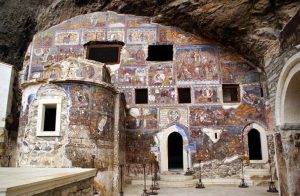

Part of the archeological site of Hierapolis

The great baths were constructed with huge stone blocks without the use of cement, and consisted of various closed or open sections linked together. There are deep niches in the inner section of the bath, library, gymnasium and other closed or open locations. The complex, which was constructed in the 2nd century BCE, constitutes a good example of vault type architecture. The complex is now an archaeological museum.

Hierapolis is located in the Menderes River valley adjacent to the modern Turkish city of Pamukkale and nearby Denizli. It is located in Turkey’s inner Aegean region, which has a temperate climate for most of the year. See Pamukkale#Geology for more detail.

There are only a few historical facts known about the origin of the city. No traces of the presence of Hittites or Persians have been found. The Phrygians built a temple (a hieron) probably in the first half of the 3rd century BCE. This temple would later form the centre of Hierapolis. It was already used by the citizens of the nearby town Laodiceia, a city built by Antiochus II Theos in 261–253 BCE.

Hierapolis was founded as a thermal spa early in the 2nd century BCE and given by the Romans to Eumenes II, king of Pergamon in 190 BCE. The city was named after the existing temple, or possibly to honour Hiera, wife of Telephus – son of Heracles by a Mysian princess Auge – the mythical founder of the Attalid dynasty.

The city was expanded with proceeds from the booty from the Battle of Magnesia in 190 BCE, where Antiochus the Great was defeated by Eumenes II, who had sided with the Romans. Thus Hierapolis became part of the Pergamon kingdom.

Hierapolis became a healing centre where doctors used the hot thermal springs as a treatment for their patients. The city began issuing bronze coins in the 2nd century BCE. These coins give the name Hieropolis (town of the temple Hieron). This name eventually changed into Hierapolis (Holy city).[1]In 133 BCE, when Attalus III (the last Attalid king of Pergamon) died, he bequeathed his kingdom to Rome. Hierapolis thus became part of the Roman province of Asia. The Hellenistic city was slowly transformed into a Roman town.

In the year 17 CE, during the rule of emperor Tiberius, an earthquake destroyed the city. In 60 CE, during the rule of emperor Nero, an even more severe earthquake left the city completely in ruins. Afterwards the city was rebuilt in Roman style with the financial support of the emperor. It was during this period that the city attained its present form. The theatre was built in 129 CE when the emperor Hadrian visited the town. It was renovated under Septimius Severus (193–211 CE). When emperor Caracalla visited the town in 215 CE he bestowed on the city the much coveted title of Neocoros, according the city certain privileges and the right of sanctuary.

This was the golden age of Hierapolis. Thousands of people came to benefit from the medicinal properties of the hot springs. New building projects were started: two Roman baths, a gymnasium, several temples, a main street with a colonnade and a fountain at the hot spring. Hierapolis became one of the most prominent cities in the Roman empire in the fields of the arts, philosophy and trade. The town grew to 100,000 inhabitants and became wealthy. According to the geographer Stephanus of Byzantium, the city was given its name because of the large number of temples it contained (again a sign of wealth).Antiochus the Great had sent 2,000 Jewish families to Lydia and Phrygia from Babylon and Mesopotamia, later joined by Jews from Palestine. A Jewish congregation grew in Hierapolis with their own more or less independent organizations. It is estimated that the Jewish population in the region was as high as 50,000 in 62 BCE.[2] Several sarcophagi in the necropolis attest to their presence.

Through the influence of the Christian apostle Paul, a church was founded here while he was at Ephesus.[3] The Christian apostle Philip spent the last years of his life here.[4] In 80 CE, he was martyred by crucifixion and was buried here. His daughters remained active as prophetesses in the region.[citation needed] The Martyrium was built on the spot where Philip was crucified.During his campaign in 370 CE against the Sassanid king Shapur II, the Roman emperor Valens made the last ever imperial visit to the city.

During the 4th century CE, the Christians filled the Plutonium (a sacred cave, see below) with stones, suggesting that Christianity had become the dominant religion and that earlier religions were suppressed. In 531 CE the Byzantine emperor Justinian raised the bishop of Hierapolis to the rank of metropolitan. The town was made a see of Phrygia Pacatiana.[5] The Roman baths were transformed to a Christian basilica. During the Byzantine period the city continued to flourish and also remained an important centre for Christianity.

In the early 7th century CE, the town was devastated by Persian armies and again by a destructive earthquake, from which it took a long time to recover.

In the 12th century CE, the area came under the control of the Seljuk sultanate of Konya. In 1190 CE, crusaders under Frederick Barbarossa fought with the Byzantines and conquered the town. About thirty years later, the town was abandoned and the Seljuks built a castle in the 13th century CE. The city was abandoned in the late 14th century CE.

In 1354 CE, the great Thracian Earthquake toppled the remains of the ancient city. The ruins were slowly covered with a thick layer of limestone.

Hierapolis was first excavated by the German archaeologist Carl Humann (1839–1896) during the months June and July 1887. His excavation notes were published in his 1889 book Altertümer von Hierapolis.[6] His excavations were rather general and included a number of drilling holes. He would gain fame for his discovery in Pergamon of the Pergamon Altar which was reconstructed in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin.Excavations began in earnest in 1957 when Italian scientists, led by Paolo Verzone, began working on the site. These studies continued into 2008 when a restoration of the site began.[citation needed] For example, large columns along the main street near the gate named after Domitian, that had been toppled by earthquakes, were erected again. A number of houses from the Byzantine period were unearthed, including an 11th century courtyard house.

Many statues and friezes were transported to museums in London, Berlin and Rome. In 1970, the Hierapolis Museum was built on the site of the former Roman baths.

After the large white limestone formations of the hot springs became famous again in the 20th century, it was turned into a tourist attraction named Cotton Castle (Pamukkale). The ancient city was rediscovered by travelers, but also partially destroyed by hotels that were built there. The new buildings were removed in recent years; however the hot water pool of one hotel was retained, and, for a fee, it is possible to swim amongst ancient stone remains.

Hierapolis was a see of Phrygia Salutaris, suffragan of Synnada. It is usually called by its inhabitants Hieropolis, no doubt because of its hieron (which was an important religious centre), is mentioned by Ptolemy (v, 2, 27), and by Hierocles (Synecd., 676, 9). It appears as a see in the “Notitiæ Episcopatuum” from the sixth to the thirteenth centuries. It has been identified as the modern village of Kotchhissar in the vilayet of Smyrna, near which are the ruins of a temple and the hot springs of Ilidja. Hierapolis once had the privilege of striking its own coins. We know three of its bishops: Flaccus, present at the Council of Nicæa in 325 and at that of Philippopolis in 347; Avircius, who took part in the Council of Chalcedon, 451; Michael, who assisted at the second Council of Nicæa in 787. St. Abercius, whose feast is kept by the Greek Church on 22 October, is celebrated in tradition as the first Bishop of Hierapolis. He was probably only a priest, and may be identical with Abercius Marcellus, author of a treatise against the Montanists (Eusebius, Church History V.16) about the end of the second century. On the epitaph of Abercius and its imitation by Alexander, another citizen of Hierapolis, see INSCRIPTION OF ABERCIUS.